Mail Loom

( By Eadwynne of Runedun. Original article published in the Scientific Caidan, Vol.1 under the name Edvin of Runeden, c. 1980)

When I first saw mail, I was understandably impressed by its beauty and elegance. I was equally impressed by the endless hours of labor put in by the makers. Lord Carl of Carmarthin, pliers flying in his blistered hand, was making a suit at my first Society event. I was hooked. There are many problems facing the amateur mail maker. Being a typical all-American medievalist, I began looking for a manageable means of mass production (7-30,000 links is no small number). By asking advice from more experienced mail makers, many problems were avoided or eased, yet some persisted. Assuming that you already know the rudiments of mail manufacture, or that you can find out easily enough, I’ll specify those problems that the loom can help remedy:

1. Opening and closing your rings quickly and precisely. Prior to knitting, every ring mush be opened. If your rings are not opened enough, they cannot be linked. If they are opened too far, they may distort or weaken. If you are knitting mail using the two-rows-at-a-time method, you will want half of your rings opened and half closed. Remember, a tightly closed ring is the key to a good quality fabric that will stay together longer and won’t “bite.” 2. Keeping your pattern clear. If you knit on your knee, or on a table, or on the rug, your mail will tend to shift around into a tangled mass of conflicting and confusing patterns. 3. Quality control. This problem is related to the last in that if you cannot see the pattern in your mail, you may not detect flaws until much later when they are much more difficult to fix. 4. Keeping the mail out of your way while you are working. As you knit, your mail will become more and more cumbersome, hindering further progress.

BUILDING THE LOOM

When Lord Elgil and I began designing the loom (his and mine are slightly different), we built it with the intention of making suits and coifs for ourselves and members of our household. As we are quite different in size, we designed it to make strips of mail to be put together in whatever form desired later. This also allowed for a small and portable loom. However, knitting strips together is no great amount of fun, so if you intend to knit large articles, knitting larger pieces of mail fabric on a larger loom may prove to be less of a headache. I should also note that we were making what was then typical SCA mail using 14 gauge galvanized steel with about 3/8 inch inner diameter rings which we wound ourselves. The procedure for making a smaller loom is below (note: I eventually made a larger loom, which I definitely liked better). My measurements may seem rather vague, but they are meant as a guide only. The dimensions which you end up with will depend upon your personal preference and on the materials you have on hand.

MATERIALS

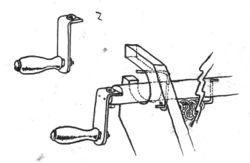

a) a 2x4 slightly less than shoulder width wide b) a ½ inch thick board cut as wide as the length of your 2x4. This will act as a base, so you will want it about a foot wide or so. c) a 1X6 about an arm span long for the uprights d) a handful of large and small nails, and maybe a couple of screws (note: screws hold tighter longer) e) Two long nails to act as ring openers and closers (up to ½ the inside diameter of your rings, I used 60D nails) f) a broomstick (or equivalent) a handspan (or about 6 inches) wider than your 2X4 for your support bar/loom arm. g) a wire clothes hanger, a welding rod or other stiff wire to mount your mail on h) one or more screw eyes to hold the removable hanging wire described above for longer hanging wires (see figure e). My original used bent wire. i) Tools: hammer, saw, jigsaw, wire or bolt cutters, a drill with a drill bit slightly larger than the wire (f) j) (Optional) Parts for the crank handle (my later versions didn’t have a crank handle): a small strip of scrap metal (see illustration), dowel (from the broomstick is fine), a wood screw, a couple of brands, a bolt ½ inch longer than the dowel handle.

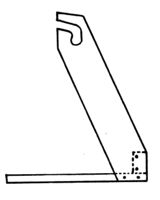

PROCEDURE Base (refer to figure A)

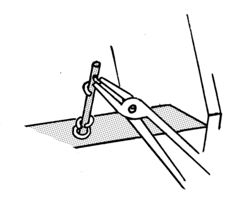

a) Attach the 2X4 flush to the outside edge of the ½ board (“b” in materials above). b) Cut the 1/6 into two equal lengths to form the uprights. c) Cut these into the approximate shape shown in Figure A (I always intended to make a set that looked like the dragon-headed prows of Viking ships, but alas, I never did. Not yet anyway). d) Attach these uprights to the base with nails or screws (screws are better). e) Nail the two large 60D nails into the 2X4, leaving several inches remaining out of the wood. These will be your ring openers/closers (see figure b) and should be at least a hand apart. You may want to place them more to one side of the loom. For example, a righthander would probably place them slightly left of center. f) Cut off the heads of the nails and break and smooth the cut edge.

Loom Arm

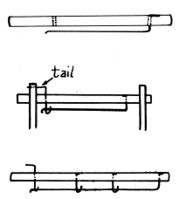

a) Drill two holes the width of your hanger wire perpendicular to the axis of the dowel, about four inches from one end and 2 inches from the other. The distance between these holes should be an inch or so less than the distance between the uprights (figure c). b) Cut and form the wire as shown in figure c. c) Cut another length of wire about 3-4 inches long to complete the assembly. This tail (shown in figure d) will act as both a support for the hanging wire and as a stop to keep your spool of mail from unwinding. The length of the wire should be ½ inch less than the distance between the two uprights. This allows you to turn the dowel freely to roll up your mail, and to catch the tail on the upright to keep the mail from unrolling. The hook allows for easy removal of the mail fabric from the loom arm. d) On a larger loom (such as on all of my subsequent models), you will want to add more support hooks (see figure e).

Illustrations

-

Figure A

-

Figure B

-

Figure C, D, and E

-

Optional Loom Handle

USING THE LOOM

When I knit mail, I pre-open and close a number of rings to speed my process later. Put a stack of cut rings onto the ring opener/closer. With a flick of your wrist, your ring is open, and closing is just as easy. You will find that the springs from which you cut your rings will be wound in a right or left=handed spiral, affecting the ease of opening and closing of your rings. Unless you wind your own springs (very easy, but that’s another article), you are stuck with this problem.

To begin knitting, put a row of closed rings on the hanging/retaining wire of the loom arm and hook the hanging wire into the hooks on the support bar. Knit your mail. When the strip gets a little too long to work with comfortably, turn the loom arm and the mail will wrap around it. When your strip is the desired size, unwrap the mail fabric and disengage the retaining wire. You can leave the mail on the arm as a convenient means of transport and storage.

The rest is History. Have fun.

End Note: I have made several hauberks, coifs, aventails and other mail garments since I wrote this article. This loom worked great for different sizes of rings and different ring materials. But the nails used for ring opener/closers were not as effective on smaller or harder rings. They were pretty much useless when I used stainless steel rings. So your mileage may vary.

As an additional note, a lot of mail is now coming from overseas manufacturers. Some of it is of good quality, and some of it is riveted which is superior to the butted mail that I have made on this loom. But there is something very satisfying about making your own armor specific to your own desires and requirements. I hope people will continue to keep this skill alive in our current middle ages.

Mail – A Short History (1981)

Mail, metal mesh body armor, was the typical armor of the warrior class in the early middle ages. However, its history is far older. Although authorities disagree on just when it was developed, it can be said with some certainty that the ancient celts had it by the 5th century BCE, and it was they who introduced it to the Romans. When Rome fell, weapons and armor became rare and priceless possessions. To the barbarian tribesmen of Europe, swords that didn’t break and shirts of iron mail were considered to be magical heirlooms. Later, as the Middle Ages progressed, guilds organized which specialized in making armor or weapons. They were patronized by the warrior class nobility in what is called the feudal era. During this time, the barbarian tribes began to nationalize. For instance, the land of the Saxons and Angles became England, and the land of the Northmen became known as Normandy, each under royal rule.

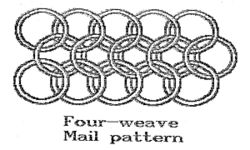

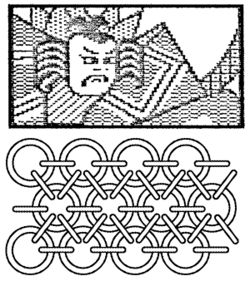

In the year 1066, a dispute over the throne of England brought England and Normandy to war. The Normans under William the Conqueror settled the dispute by killing the Saxon contender for the throne, Harold Godwinson. They set up their own dynasty. The armor worn by the warrior class from each side was similar: a knee-length hauberk (mail shirt) and a conical helmet. The Saxons usually preferred a round shield since they fought on foot. The Norman, being horsemen, preferred the longer kite-shaped shield. This style of armor had become common in so many different places that it has become known as “the international style.” This type of armor was illustrated in tapestries and manuscripts from the 9th to the 13th century. Gradually as European technology improved, mail was first supplemented and eventually superseded by plate armor as a primary means of defense. The use of mail continued, however, up until the beginning of the modern era where gunpowder changed the face of warfare. Europe was not the only place mail armor was used. During the times of the Crusades the Armies of Islam often used light mail as a defense. Rather than each ring being riveted like much of European mail, it was usually butted or overlapped, and therefore less protective. In Japan mail was only used as a supplementary defense and it never gained the wide use that it did in Europe. The Japanese developed several weave patterns different from the typical four-in-one European pattern. These patterns seem designed to be as decorative as they were protective.