A Short History of Saint George: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

(1) From: Cut and Thrust Weapons, by Eduard Wagner. Spring Books, Frury House, Russell Street, London WC2. Translation ©1967 by Jean Layton; English Edition ©1967 Artia Prague | (1) From: Cut and Thrust Weapons, by Eduard Wagner. Spring Books, Frury House, Russell Street, London WC2. Translation ©1967 by Jean Layton; English Edition ©1967 Artia Prague | ||

<i>The author, Theign Eadwynne of Runedun, lives in the Barony of Dreiburgen in Caid. Ted Hewitt lives in San Jacinto, CA USA.</i> | <i>The author, Theign [[Eadwynne of Runedun]], lives in the Barony of Dreiburgen in Caid. Ted Hewitt lives in San Jacinto, CA USA.</i> | ||

[[Category:Articles]] | [[Category:Articles]] | ||

Revision as of 10:39, 28 April 2022

A Short History of St. George by Eadwynne of Runedun

The History

The History of the real St. George, and there was a real St. George, is shrouded in mystery and legend. He is remembered on his Feast Day, on the twenty-third of April.

In the East, St. George is known as "the Great Martyr," and "Victory Bringer." According to the writings of St Jerome (d. 420 AD), he was a soldier who was martyred for his faith at Lydda in Palestine in the 3rd century AD. From that time, churches were dedicated to him in Jerusalem. St. George was described as a successful Roman army officer and at a young age he rose through the ranks to the rank of tribune. However, the Roman Emperor, Dioclesian (d. 313 AD) grew suspicious of Christians because they would not sacrifice to the Roman Gods. He began a series of persecutions and had his own Praetorian Guard destroy the Christian Cathedral at Nicodemia. During this persecution, around the year 302 AD, St. George sold his possessions and gave the money to the poor, freed his servants, put aside his office and then complained personally to the Emperor of the harshness of the decrees and the violence against Christians. St. George was thrown into prison and tortured. His faith never wavered and the following day he was dragged through the streets and beheaded. It might sound strange that a man who gave up his military career and died by torture and in poverty and disgrace should become the model of the Christian fighting man. But it is important to remember that the fight of St. George was not simply against a physical foe, but also for an ideal for which he was willing to give his last ounce of strength and his final breath.

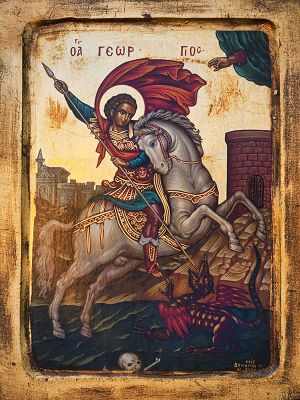

The idea of the spiritual warrior fighting against evil is a powerful one. The knight and dragon shown in his images were originally an allegory of his spiritual fight against Dioclesian and the wrongful persecutions. Personifications of evil as a serpent are found several times in the Christian Bible. And, since most people in early times could not read, the Church used images as teaching lessons and images of St. George reminded people to always resist evil both in society and within themselves. The Icon of St. George fighting a dragon was seen as an image of holy truth. It represented the struggle of all men. In Islam, such a struggle is called the Jihad, a spiritual warfare. Islam has their own version of St. George in the person of Al Khadir, the Green Knight.

From the beginning, the image of St. George inspired stories and legends. One of the earliest is the "Passio Georgi," and it is full of stories of St. George's bravery in battle, and provides grisly details and miracles associated with his martyrdom. It was so popular that in 494 AD, the Catholic Pope Gelasius I had to list this story as "apocryphal," and not used for official teaching. St. George's story became widely told and spread beyond Palestine and the Middle East. It was brought into what is now Russia and the Ukraine, where he became the patron saint of Moscow, surviving even during the time of official Communist atheism. He was patron of cities across Europe and of Ethopia in Africa. But the story of St. George entered Europe with the return of the Knights of the First Crusade in the 11th century.

The Crusades

After the Roman Emperor Constantine's Edict of Milan legalized Christianity, the Holy Land became a pilgrimage site for Christians throughout the vast Roman Empire, and Jerusalem was its most important site. By the 7th century AD, the Islamic Rashidun Caliphs had captured portions of Palestine previously held by Byzantium. Jerusalem is important in Islam as the site of the ascension of the prophet Muhammad into heaven. In 1009, Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (the Church built over Christ’s tomb), and a renewed persecution of Christians. Many Christians were killed. The Emperor of Byzantium, Alexus I, asked for the assistance of the Catholic Pope in Rome. Pope Urban II responded to this request by his “Call to the Crusades,” for soldiers to bear the Cross of Christ to free the Holy Lands from oppression. The response to Pope Urban II was nothing short of astounding. Preachers such as Peter the Hermit and others rallied the Knights and men-at-arms from across Europe. To finance their journey, these militant pilgrims sold or borrowed against their goods and lands, put on the cross of the Christian Crusader and set out to the East. The first siege of a Muslim city was at Antioch, which had until recently been under the control of the Byzantine Empire. The siege lasted nearly a year and the Crusaders were eventually successful. Enemy reinforcements arrived, and the besiegers became the besieged. When all looked lost, a monk traveling with the Crusaders named Peter Bartholomew had a vision of the Holy Lance which had pierced the side of Jesus at the Crucifixion. The Crusaders dug at the location told of in the vision and they found a lance head of ancient origin. Re-invigorated with what seemed a miraculous gift from God, they redoubled their efforts. They stormed out of the city to victory.

Contemporary reports say that many in the Christian army saw St. George himself participate in the battle assuring them victory. The battle for Antioch became legendary, and told of throughout Europe in songs called "chansons de geste." St. George's part in the story made him patron saint of Christian Knights throughout Europe, particularly of the Crusaders. He was painted as a young and valiant knight bearing the red Crusader's Cross. Thus the Crusader Cross became the Cross of St. George. St. George was still shown slaying a dragon, but a new character was added to his image, that of a royal maiden in chains, symbolizing the Church in captivity. So it was that the Palestinian Roman soldier St. George became a Crusading Knight.

St George and the Dragon

In 1266 AD, Jacobus de Voragine published "The Golden Legend" which told of many fantastic exploits of many saints. The story of St. George was further embellished with stories of St. George fighting a real dragon and saving a King's daughter. As the story goes, St. George in his travels as a knight-errant comes to the city of Silena in Libya in North Africa. Its citizens, who were not yet Christians, had fought a dragon without success and could only survive by feeding it one of their citizens. The victim was chosen by lot. At last, it was the King's daughter, Cleodolinda, who had been chosen. She was dressed in her finest clothing and chained just outside the city gate. St. George happened to be traveling by and heard her crying. He asked why she was chained and why the townsfolk were watching from behind their walls. She told him of the dragon and he vowed to slay it. Making the sign of the cross on his chest as protection, he rode against the dragon and pierce it with his lance. He freed the princess and paraded the wounded dragon into the town, exclaiming, " I have been sent by the Lord to free you from the tyranny of the dragon. Be baptized and I will kill the dragon." According to the legend, the whole town of twenty thousand men, not counting women and children, converted to Christianity. St. George then fulfilled his promise. This fanciful legend was an allegory or pious fiction meant to teach a Christian truth. Lord Baden Powell, founder of the Boy Scout Movement, used this story in exactly the same way it was used by the medieval storytellers, to excite his listeners to be true to God and to attempt great deeds against all odds.

St. George as Patron of Soldiers, Sailors and Fishermen

In a battle against the French near Kochersberg, an Imperial officer was carrying a thaler in his coat pocket (from where we get the word, "dollar"). In battle, the he was shot and knocked off of his horse and fell to the muddy ground expecting to die. To his surprise, he found himself breathing and his heart still beating. He checked his chest and found his thaler, dented by the musket ball which had hit him. Now this particular thaler was from Mansfeld, Germany and St. George was the patron of the Count von Mansfeld. On this coin was an image of St. George. At another time, a Saxon Colonel of the Sachsen family, von Lisbau, had a Mansfeld Thaler sewn into his clothing. He was shot twice during the campaign but was miraculously protected by a Thaler blocking the bullet. Of course, stories like this get around quickly. By the Thirty Years war against the Turks, every officer and soldier wanted to have a Mansfeld thaler as a protective amulet. Demand soon outstripped supply and enterprising coin makers began making medals based on the Mansfeld thaler. On the obverse was an image of St. George surrounded by the Latin words, "S. Georgius, Equitum Patronus," or, St. George patron saint of horsemen (a common word for knights). On the reverse was an image of Christ sleeping in a boat buffeted by high waves with his panicked apostles trying desperately to wake him. Around this image were the words, "In tempestate, securitas." These words have a double meaning. Tempestate can mean either storm or trouble, so the meaning could be read as security in times of troubles. These antique medals can still be found as they became widely popular among soldiers, sailors and storm-tossed fishermen across the face of Europe.(1)

St. George in England

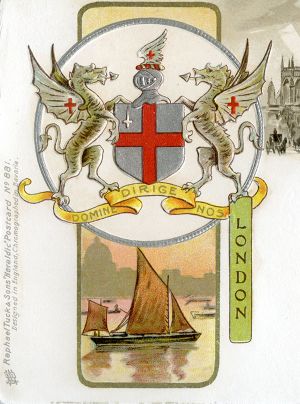

St. George was not the original patron saint of England. That honor goes to St. Edmund (d. 869 AD) and St. Edward the Confessor (d. 1066 AD), who were both kings of England. King Edmund was dispossessed and martyred, and King Edward "confessed" the Catholic Faith. Like most of the Chivalry of Europe, the Kings of England considered St. George their particular saint. King Edward III (d. 1377 AD) had a particular devotion to St. George. A manuscript Known as the Milemete Treatise shows an armor-clad St. George bestowing a shield bearing the royal arms to the king. St. George was the picture of the ideal knight which all the chivalry should strive to be. Edward founded the most prestigious order of knights in England, the Order of the Garter on St. George's feast day, April 23, 1344 AD. He placed it under the protection and patronage of the Virgin Mary, St. Edward the Confessor and of course, St. George. And from that time, the Kings of England regularly called upon St. George in battle.

In 1415 AD, during the Hundred Years War, King Henry V and the English army laid siege to the French town of Harfleur. The English were outnumbered by heavily armored French Knights. Just when the battle seemed hopeless, a vision of St. George was seen entering the battle on the side of the English. They won the day and Henry commanded that the flag of St. George be flown over the town. Henry declared that St. George was the new official patron of England. There was a joyous victory parade in London and a statue of St. George as an armored knight was set on top of a tower. Banners honoring St. Edmond, St. Edward and St. George hung on the walls. Since the victory was attributed to the aid of St. George, his story naturally became more popular than ever. The story of St. George was told and retold and even became part of the popular plays held around Christmas every year. St. George's feast day, April 23rd, marked the end of winter and so it began the Spring-tide celebrations. Parades were held featuring an armored knight and a dragon. In larger towns such as Norwich, the processions might be huge and the dragon would spit sparks and smoke. It would end with a mock battle between St. George and the dragon, after which the crowd retired to the Church for a more religious remembrance. King Henry VIII also respected the ideal of St. George and as a young man Henry enjoyed the sport of jousting. Henry added the red cross of St. George to the English flag and issued coins with St. George's image on them. In a dispute with the Catholic Pope, King Henry declared himself head of the Church in England in 1534 AD. The old Catholic patron saints, King Edmund and King Edward became embarrassments to the new Anglican king. He abolished nearly all religious holidays, but not St. George's day. But even so, St. George's day lost much of its religious character and became much more of a civic holiday. St. George himself became a more fanciful romantic character. He became identified with the chivalric legends of King Arthur and the valiant Knights of the Round Table rather than as a Catholic saint. Reinvented as a naked Greek horseman by engraver Benedetto Pistrucci, St. George continued to grace English coinages through the Victorian Era and for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012.

(1) From: Cut and Thrust Weapons, by Eduard Wagner. Spring Books, Frury House, Russell Street, London WC2. Translation ©1967 by Jean Layton; English Edition ©1967 Artia Prague

The author, Theign Eadwynne of Runedun, lives in the Barony of Dreiburgen in Caid. Ted Hewitt lives in San Jacinto, CA USA.