Embroidery & Decoration In Scotland and Ireland of the 15th and 16th Centuries

In Scotland and Ireland of the 15th and 16th Centuries

Written and illustrated by Jennet Jowan Truro (© 1990, Janet Cornwell)

...with thanks to the many fine authors mentioned in the Bibliography, and, of course, their sources, and all our handcrafting ancestors

done for

SYMPOSIUM ON THE TEXTILE ARTS OF 15TH AND 16TH CENTURY IRELAND AND SCOTLAND, March 11, 1990,

NEEDLEWORK AND DECORATION

Attempting to recreate or even describe the "soft crafts" of this time and place has proven to be a real adventure, as we are hampered by a sad lack of surviving examples as well as by a scarcity of good contemporary description. Nonetheless, enough bits and pieces of information have been recovered, both from these areas and from the rest of Europe with which the Renaissance Scots and Irish traded, that it is possible to make a good guess as to the tools, textiles and techniques most favored by these folk.

The Four Cultural Areas

It is necessary, in dealing with Scotland and Ireland, to realize that there were in the 15th and 16th centuries essentially four culturally different, though interrelated, geographical areas.

- Ireland had remained essentially Celtic since that people conquered the island around the 4th century BCE. The Romans never got there. The Vikings raided widely and founded the few towns to be found in Renaissance Ireland, but never fundamentally disturbed the customs of the country. Visitors from Europe fund the Irish sophisticated, savage and fascinating.

- The English monarchs had frequently declared themselves Lords of Ireland, but they had really established control only over a small area called the Pale, near Dublin. It had the character of a colony; as near as it was to England, it ha its own styles and systems that were distinctly un-English.

- Highland Scotland was colonized by Gaels from Ireland around 400 CE. These people seem to have absorbed certain aspects of the native Pictish culture, even though they obliterated most evidence of it, and maintained close ties with their own Irish cousins. Western Scotland was also affected by several centuries of occupation by Scandinavian lords. Poverty and lack of roads inhibited the spread of goods and ideas here, though trade centers such as the Orkney Islands showed an interest in the new.

- The Scottish Lowlands in the south, on the other hand, had never bee truly Gaelic--speaking, their early British-Celtic peoples having been fought and walled off by the Romands, and then replaced first by Danish and Anglo-Saxon immigrants and finally by Anglo-Norman feudal lords. This area was more commercial than the others, maintaining close trading connections with France and the Netherlands and following their styles.

Each of these areas had customs of its own, though of course they all had some trade and communication, as well as less friendly relationships, with each other. Each defeloped its own decorative styles, thought many of their implement and resources were the same.

For Historical Re-Enactment Use...

For those who simply would like to add a bit more realism to their portrayal of theatrical or historical re-enactment characters, the text and illustrations here should be sufficient. Regional differences will be mentioned so the reader may determine which items pertain to which historical characters.

Those interested in studying specialized and decorative textile work are recommended to the fine and fascinating books in the Bibliography (some in print, some available in local public and university libraries, and some available by arrangement with private parties in various historical groups. and from there to the original sources and museum pieces which may found, especially in the British Isles. There is a great deal to be learned and shared!

EMBROIDERY

We have few samples, descriptions or pictures of Scottish and Irish clothing and goods of 1400's and 1500's, but many show or mention embroider on clothing and houshold goods. Thus we know that embroidery was practiced in all four areas, though to different effect.

TOOLS:

Few needleworking tools have survived since four or five hundred years ago, as useful things tended to be used until worn out, and not protected or hoarded. We do have some pictures, examples, and descriptions specifically from Scotland and Ireland. Information from England and the Continent also gives hints of what else might have been available, especially in the Pale, and the Scottish Lowlands. In the Gaelic-Speaking areas the people wer both quite poor and far from trade routes, thus not likely to take new tools or methods even when they were known elsewhere. Where tools were needed and unavailable, they were often improvised.

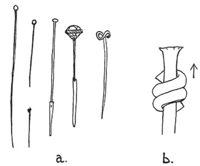

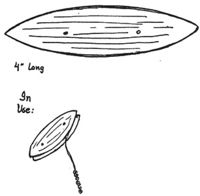

Needles: In this time and place it wasn't easy to find good needles. Homemade needles were crafted of thorns, fish bones, bone, antler, ivory and shell. Bronze needles made by craftsmen survive, though many of them are large and fairly crude. For made by craftsmen survive, thought many of them are large and fairly For coarse sewing where were awls. But the best needles, the ones preferred for decorative sewing, were made of steel. They were prized possessions, very scarce and expensive, and treated with extreme care. Metal needles might be made with a slight kink to keep the precious implements from slipping out of the work piece or out of a carrying case (Fig. 1).

An indication of the value placed on needles comes from the old Brehon Law of Ireland: one who wrongfully kept another's needle was fined a yearling calf for a common needle, a two-year old heifer for a needle used for ornamental work on mantles, and an ounce of silver for an embroidery needle.

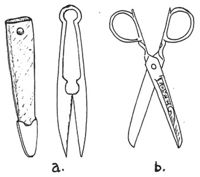

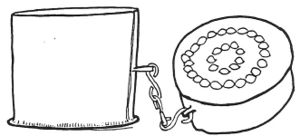

Needles were usually kept in needle cases made of wood, bone or metal, often tubular, and threaded onto a ribbon or strip of leather. This had a small piece of fabric sewn to one end into which the needle was struck. Hung by its ribbon from the owner's girdle, the case slipped up to reveal the needle, then down to rest against a ring or stop. Needle cases matched their owner's station" great ladies might have had elegant, bejeweled, gold and sliver cases to hold their fine needles, where a countrywoman kept her bronze or bone needle in a wood or bone holder carved by her husband or son. (Fig. 2)

Bodkins, large, needle-like implements for threading ribbons, cords and laces through garments and purses, were used both by men and by women. They too were made of bone, wood, metal, or even tortoise shell, and were sometimes very ornately engraved. Some had ear-spoons on the "eye" end. (Fig. 3)

Pins: Pins were made locally of the same materials as needles. Craftsmen also made individually forged pins of bronze, fashioning points using grooved bones and small files, attaching separately made coiled-wire pinheads with tin solder. (Fig. 4) Metal pins were being made in England before Richard III's time, but the finer French pins were preferred. In any case, they were expensive, but apparently easier to get than needles. 10,000 pins were provided for the young Mary Tudor. Some pins were very long and were used to hold draperies and the like together permanently; these were often paired with protective end covers that were sewn to the cloth. Pins were kept struck in pin cushions and pin-pillows made of the very best remnants of fabrics and embroidered work.

Scissors and Shears: Spring-type shears as well as scissors with pivoted blades were known to be in use in Roman times. On the Continent, fine scissors for "cutwork" were developed in the 16th century, but they were easily found in England after 1650. Thus it is probably that only Scottish and Irish ladies of the very highest rank would have used them for embroidery. Most people would have had small iron shears, probably with steel blades, kept in a leather slipcase. (Fig. 5)

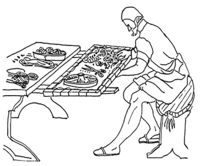

Frames: Frames were used to hold cloth taut while embroidering. They ranged in size and materials from small, hand-held, nesting rings made of horn, to great standing frames made out of adjustable wood pieces, on which an entire pattern piece for a coat or dress might be worked. The wooden frames, usually held or rested horizontally, were often adjusted by means of pegs, and the work piece laced or stitched to the wood. (Fig. 6, 7)

Thread Winders: Thread for embroidery was frequently kept on a thread winder, a small, geometrically shaped piece of wood, horn or bone. Very short thread pieces might be looped onto a stick or through a ring.

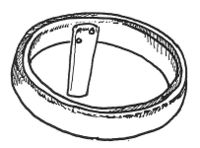

Couching Tools: Tatting-type shuttles were made in creating lengths of knotted thread for use in couching (see Techniques, below), though tatting itself was unknown at this early date. The shuttles were larger than tatting shuttles, being about two inches wide by for to six inches long, and they had more space between the sides to accommodate cords and homespun yarns. (Fig. 8)

"Broches" or spindles were used to handle gold or silver thread. The metal thread was wound around the spindle and slipped through a slit at the pointed end of the implement and thus applied to the surface to be couched. This prevented the hands from touching the metal and tarnishing it. (Fig. 9)

Pattern Sources: Pattern books came in during the early 1550's in Germany and Italy, and were well-known in England by the century's end. They were very costly, therefore pretty well restricted to use in court circles. Elsewhere patterns were handed down in tradition from one needleworker to another, often making certain stitches or arrangements particular to one family or locale. Examples might be stitched onto cloth strips for reference, the ancestors of the "sampler" as we know it.

TEXTILES AND THREAD

There were two types of textile fiber native to Ireland and Scotland at the time: wool and linen. Silk and cotton had to be imported, silk particularly was expensive but available, especially towards the end of the 16th century.

Linen: Flax for linen was grown in both countries, though Scotland produced neither the quantity nor quality that Ireland did. However, Scotland had a longstanding trade agreement with the Netherlands, exporting coal and hides and importing fine European linen, so especially for the upper classes, excellent material was available for needlework. Linen was used for all manner of clothing and household gear, from the great saffron linen shirts of the "wild Irish," to the elegant English-style doublets, to church vestments, banners, curtains and bed hangings.

Wool: Fine woolen material used for Scottish court hangings was richly decorated. Bed valances and cushions were made of canvas embordered in silks and colored wool, and fine worsted yarn was used for making decorative fringing. The Irish men's' jackets of the 16th century, brightly embroidered or appliqued, were made of thickly-napped woolen material called frieze, as were the Irish cloaks so often described as fringed and "set out" with colors. Remnants of colored wool, called "thrums," were got from weavers and gladly traded from one needleworker to another.

Metallic Threads: Gold and silver embroidery on heroes' clothing is noted in ancient Irish sagas, which is not surprising in light of Ireland's early reputation as a center of precious metal working. In Dublin the professional embroiderers, men and women, belonged to the Guild of Smiths, which also included makers of wire and metal thread. Mary, Queen of Scots, used threads of gold, silver and "false gold" in working her copious stitchery.

COLORS

Thread bought specifically for embroidery was usually purchased already dyed. Linen and wool thread made locally could be dyed an astonishingly array of hues with local dyestuffs, and of course the prettiest, rarest colors went to those who could pay the best (the church or the laird, for instance). But almost everyone had a good selection of reds, yellows, blues and purples among the bits and pieces from the local weaver's scrap basket, or from picking apart old garments or from trading lengths with their neighbors. A good needleworker commissioned to do a piece for the laird always had the best available yarns, no matter what the stitcher's own station.

A HISTORICAL INTERLUDE...

EMBROIDERY IN IRELAND

Embroidery was an honored art among the Irish, both as a profession and as a skill of noblewomen. There are many reverent references to it in the ancient Brehon Laws: it was said that embroideresses "deserve more profit than even queens."

Needlework was considered one of the six proper gifts of women, and chieftains' daughters fostered to other noble houses were expected to be taught the arts of "sewing, cutting-out and embroidery." Wives of heroes brought their needles to feasts. When the legendary hero Cuchulainn came to woo Emer, he found his future wife teaching embroidery to her foster-sisters. (Later he explained a fling with a fairy-woman on the grounds that she was skilled at fine needlework, an excuse which did not impress Emer at all.)

At the great triennial fair held anciently in Leinster, there was a special place, the "slope of embroidering women," where embroideresses practiced their craft for all to see. In the late 1500's, poet Tadgh Dall O h-Uiginn praised the lovely maidens making gold fringes on the ramparts of Maguire's castle in Enniskillen. (Gold and silver embroidery, and the making of gold fringes, was known in Ireland from the 10th century on.) The pre-Norman Irish tunics were described as embroidered "from knee to ankle," while the brat (mantle) was decorated at the borders and angles.

Yet this longstanding tradition seems to have waned almost completely by the 16th century. Drawings and descriptions from the 15th and 16th centuries do not indicate much decoration on any garment other than the brats and the men's jackets. Pictures by Derricke show almost no embellishment of any kind on any Irish garment, though such is shown on English clothing, cushions and pavilions in the illustrations. This ornamental degeneration is possibly due in part to the disruption of the Irish culture, especially the nobility, during the Elizabethan wars. Certainly that continuous conflict destroyed much wealth in all sectors of the Irish economy by the end of the 16th century.

It is always possible that fashion simply drifted away from the use of lavish decoration. The causes are certainly not clear. But it is notable that, even in pictures of wealthy townspeople, ornamentation of garments was not often shown. Oddly enough, this conflicts with written descriptions, especially of townswomen in the English Pale. Such descriptions come in the form of prohibitions against finery: "No woman use or wear any kyrtall (skirt) or coat tucked up, or embroidered or garnished with silk, nor couched..."

Such prohibitions as the above, pronounced by Henry VIII around 1539, were meant to keep colonists from "going native" and affecting such Irish costume as might startle or offend English or European visitors. Prohibitions would not have been needed unless the offenses were being committed, so it is probable that there was at least some "unseemly," lavish embroidery being practiced.

In the Irish towns (of which there not many at this time), much of the embroidery was being done by professionals. Embroiderers of both sexes had belonged to the Dublin Metalworkers' Guild since its chartering in 1474, and in 1498, embroiderers were responsible for supplying "well-appareled" figures of the Holy Family for a civic Corpus Christi production.

In the late 16th century the local Irish trade suffered, due to a fashion of English imports; also, under English administration, the guilds were pressured to restrict their membership to hose with English names or creed. Still, they did find ways of admitting native ("mere") Irish members, and the professionals did continue. Elizabeth Boyle assumes in Irish Flowerers that "craftsmen both in England and in Ireland occupied themselves with large hangings and badges, heavy applied initials, formal costume, official bags, heraldic work and ornamental horse furniture something like the 'bright embroidered headstall' described by Spenser in Book V of the Faerie Queene."

It is encouraging to note that some interest and skill in embroidery remained after the Tudor ravages. The wife of the first Protestant Bishop of Derry, a Mrs. Montgomery, described middle-class women wearing embroidered jackets and headcloths of local make in 1606, and at least two examples of extravagantly embroidered and appliqued linen jackets date from the 17th century. Also, even into the 1500's, narrow fabrics were joined with embroidery rather than seams.

SCOTTISH EMBROIDERY

Margaret Swain calls it "unrealistic" to look for any distinctly different Scottish embroidery style, since the British Isles shared European tastes and fashions. It is fair to not that Scottish embroidery before 1600 had more in common with developments in France and the Netherlands than with English trends. The pity is that so little early Scottish embroidery is left that it is almost impossible to determine locally popular or traditional native usages.

There are tantalizing hints of embroidery use in Gaelic-speaking Scotland, such as a notation of "the Phrygian art" used in Highland women's costume, which may be a reference to embroidery. However, we have no surviving examples or illustrations to substantiate or refute that possibility, or to show what kind of designs might have been used. It has also been noted by Bishop Lesley in 1578 that Scots "joined the different parts of their shirts very neatly with silk thread chiefly of a red or green colour." That still does not prove any type of ornament. It seems rather likely that embroidered clothing was not much used in Scotland, outside of such things as sleeves for court dress.

Embroidery was widely used on hangings, cushions (many of them), and other household gear as well as for church veils, vestments, and the like, but few of these objects survive from pre-Reformation Scotland. This is both a result of the Calvinist zeal for destruction of all things Popish and luxurious, and a consequence of native Scottish practicality. Vestments and furnishings of the church were sold for their value, destroyed for their symbolism, or more often, cut up to make new items. Even Mary, Queen of Scots, who had among her priorities the refurbishing of badly neglected embroideries in the royal chambers at Holyrood, "recycled" a number of embroidered copes, chasubles and tunicles into bed furnishings for her two husbands.

Among the items which do predate the Reformation are two banners, one the "White Banner of Mackay" from the early 1400's, and the other the "Fetternear Banner" from the early 1500's. Both show excellent workmanship with the needle, though the earlier one is of dubious artistic or heraldic virtue. There are also a few exquisite ecclesiastical embroideries surviving, such as a chalice veil of fin linen worked with a Psalm and border in red silk and silver thread.

Scotland did not have the professional workshops of the English, nor the embroiderers' guilds of Ireland. There are records of individual citizens taking on embroidery projects, such as the wife of Gerard de Haustan embroidering a mortcloth for the Metalworkers' Guild in 1497. The Crown enjoyed the services of hired embroiderers; a certain John Young was embroiderer to James V, while Mary Stuart had both a French needleworker (Pierre Oudry) and a native Scot (Ninian Miller) in her employ. (The latter set up his own shop in Edinburgh when Mary departed for England in 1568.)

Much of the embroidery done in Scotland was done by and for the noblewomen, as house furnishings. Some of these pieces are astonishingly intricate. Mary, Queen of Scots, during her long years of captivity and exile, came to epitomize the industrious Scots needlewoman. But her cousins in their houses and castles stitched diligently as well, leaving us many treasures.

TECHNIQUES

Stitches Many of the same stitches were used in both Scottish and Irish embroidery, and they reflected those generally used throughout Europe. Each country had some special stitching, though it was particular to that local.

Frequently used stitches in Ireland were the chain, buttonhole, stem, satin and braid stitch. Couching was much used, as was applique (see below). A stitch which later became popular elsewhere as the "Irish Stitch" (a long stitch taken over five or more threads) is not certain to have originated in Ireland or been especially in favor there. Some attempt was made to start an industry in "Turkey work," or knotted pile carpetmaking (usually carpets for tables, not floors), but this didn't catch on. One technique can be noted as especially and historically Irish, however, is the art of drawn-thread work.

Couching and split stitch seem to have been popular everywhere in the 15th and 16th centuries, and no less so in Scotland. Satin stitch and tent stitch wwere used extensively, and Mary, Queen of Scots, used petit point, cross stitch, and occasional chain stitch and braid stitch. The Fetternear Banner is unique in Britain for using double running stitch for both outline and filling. A particular variety of tent stitch, which gives the appearance of chain stitch, was used in some of the finer Scottish embroidery panels.

Most of these stitches are adequately described in any good book on needlework. It will profit to take a closer look at the more unusual characteristics and methods, however.

Joining: Fabrics woven on hand looms were rarely more than a yard wide, and after being fulled or "waulked" the finished pieces were even narrower. In Ireland the cloth was chronically narrow; in the 17oo's it was noted that some cloth was only 22 1/8" wide, despite an order enacted in 1635 that cloth was to be woven at least 3/4 of a yard in width. So to make almost any kind of garment (also sheets, draperies, and so on), lengths of fabric had to be joined. Rather than leave a bulky seam, the joining was often made with embroider stitches (or in Ireland, with drawn-thread techniques). This would accord with Bishop Lesley's reference to red and green threads being used to stitch together the "parts" of Highland shirts. Exactly which stitches were used is uncertain, but those used for drawn-thread work, or something like herringbone or open Cretan stitch, would be logical choices.

Couching: The application of one thread to a surface by stitching it down with another was widely known from early times. This technique allows the full use of metallic, expensive or bulky thread, without wasting any of it on the back side of the workpiece. Techniques already mentioned include couching of knotted thread into linen, of which we have at least two Irish examples, and couching of gold and silver threads, which was said to be especially popular in the 15th and 16rh centuries.

In Scottish embroidery, laid work (couching done in close-set, parallel rows) was used for filling in large areas. In one Scottish example from a tomb dated 1547, these couching stitches are interlaced at the back of the embroidery. This may be intentional, to hold the piece together or to provide extra strength on delicate fabric, or it may be quite incidental to the way the needle was held when taking deep stitches over heavy thread.

It was also usual for couched areas (in fact all "filled" sections) in Scottish embroidery of this period to be outlined, usually in silk. Couching from the underside of the fabric seems to have been normal usage in Britain until the 14th century; after that, the surface method was used.

Double-Sided Stitches: A number of these stitches were used in Scottish embroidery, probably because 1) some items, such as banners, would be seen from both sides, 2) on fine fabrics such as ecclesiastical linens, any stitch tanken on the underside would show through to the surface, and 3) the needlework was done by very tidy stitchers.

The Fetternear banner, it has been mentioned, was done entirely in double running stitch (Holbein stitch), best known in blackwork. Here it has been used in a unique way, as both outline and filling, a technique which is not known in other contemporary work. although this hanging is probably designed to show from one side only, the back of the work is as neat as the front.

The satin stitch used to work the White Banner of Mackay (which du to preservation method can only be viewed from the front) is stitched precisely and skillfully, and may have been intended to be seen from both sides.

Several stitches used in Europe were designed to be seen from either side. Some showed the same design on both sides, but one, for example formed cross stitch on one side and a square pattern on the other.

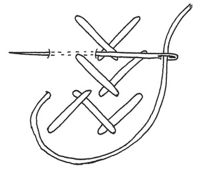

A Scottish Filling Stitch A special type of stitch that seems to be particular to Scotland at this time is found in a set of valances (possibly part of bed hangings) made in the mid-1500's for Sir Colin Campbell of Glenorchy and his second wife, Katherine Ruthven. The texture is said to look like chain stitch from the front, but is actually formed of rows of overlapping diagonals taken in alternating directions (see right). It is worked in vertical stripes on canvas. The same stitch is used for a large panel that may be a table carpet, along with some other valances.

Applique: In Scotland, at least, there was a distinction made between what was "sewn" (meaning embroidered) and what was "broidered" (meaning appliqued). However most applique work also involved a great deal of decorative stitching, and did not merely consist of pieces patched onto a ground. Wall hangings were made of black silk appliqued to a red woolen background, with the applique "sumptuously" stitched with floral designs in yellow silk. Cushions in Edinburg Castle in 1578 were appliqued with cloth of gold, and Mary Stuart brought from France bedhangings appliqued in red, blue, yellow and white satin. Applique was also mentioned as having come from cut-up vestments, as described earlier.

The Irish men's jacket, or ionar, was described as being appliqued with colored or gilded leather ("shecklaton/checklaton"), usually in designs that the Englsh found garish and offensive. Spenser despised the fashion as looking "like a player's (actor's) Painted coat." It is knot known whether the ionar decoration included embroidery on the applique or not, just as it is not clear whether the "diverse colours" mentioned as edging on the mantle were appliqued, embroidered, woven in, or attached with braid or bands. (Fig. 11)

Quilting: Quilted military garments were known from early descriptions and representations of Scottish and Irish soldiers. (Fig. 12) Not only was the padding under mail and armor quilted, but also ordinary clothes seem to have been sewed in layers, as John Major says in 1512 that Highland Scots are clothed "with a linen garment manifoldly sew'd" -- unless what he was describing was military dress. Spenser also maintains quilted armor in the Faerie Queen.

In the Anglicanized areas, it is possible that people were wearing such items as quilted nightcaps and petticoats, as quilted clothing of all kinds was known to be worn everywhere in England. Court clothing in Scotland included such refinements as quilted sleeves, echoing the fashion at the English court.

Though quilting was more commonly used for clothing than for bedcovers, the latter were also known in England and Wales -- at castles such as Powys (1551) and Carew (1592), quilts colored red, yellow, black and white were listed among the furnishings. The usual material was silk, or a silk material called sarsenet; silk was common enough, though confined to the nobility. There seem to be no specific references to Irish bedquilts, but one quilted taffeta bedspread in Scotland was known to have come to a bad end when it was blown up, along with Darnley's bed, in 1567.

Decorative quilting was often done using backstitch. In the 16th century, colored stitching came into vogue, replacing the earlier, plainer approach. At the same time the 15th century style of padding quilted designs with soft wadding or stuffing gave way to a fashion for padding with cord.

DESIGNS AND PATTERNS

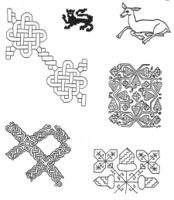

It is disheartening to some to know that in the 15th and 16th centuries, the vogue was not for "Celtic interlace," though patterns of that sort are seen in many contemporary embroideries such as the Fetternear banner and Anne Bostocke's unique sampler. (Fig. 13) (Mrs. Montgomery reports from Derry in 1605 that "geometric" and "coiling" designs were becoming fashionable again, and it is tempting to believe the ancient designs were reappearing; but the Irish embroideries we have from this period show the "coils" to be mainly stems enclosing flower.)

Far more popular, from the evidence we have, were natural and floral designs. The jackets of the Irish men are decorated with twining stems and flowers. (Fig. 11) In the Scottish embroideries of court and nobility, patterns taken from nature, myth and Biblical incidents predominate, thought the mythical and Biblical figures are often dressed in French costume of the time.

Mary, when she was reigning Queen of Scots, requested and got a royal embroider to draw up patterns for her. During her long imprisonment she often worked with Bess of Hardwick, who had the services of an embroiderer, to devise designs for her handiwork. Favorite motifs were birds, animals, flowers and vegetables, and she often added her initials of signet. (Fig. 14) She also worked visual puns called "emblems," which depicted Latin mottoes in obscure ways.

Both amateurs and professional embroiderers used many heraldic and armorial designs , especially for hangings and bed furnishings for noble houses.

Pattern books have already been mention as available to the wealthy, and for the lower classes there were sample pieces. It is said that in Ireland there were leather patterns that needleworkers followed. In any case, the designs were drawn, rather than counted and were translated into whatever stitch in outline by the designer, and the colored parts and ground filled in by the needleworker.

Although there is a dearth of examples and descriptions from this era and area, enough had been preserved or reconstructed to allow present day students and stitchers to make quite acceptable period pieces, and to develop more designs. Please do!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Boyle, Elizabeth. The Irish Flowerers. Belfast: Ulster Folk Museum and Institute of Irish Studies, 1971.

- Colby, Averil. Quilting. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971.

- Dunbar, John Telfer. Highland Costume. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, Ltd., 1977.

- Groves, Silvia. The History of Needlework Tools and Accessories. London: Country Life Limited, 1966.

- Key, Dorothea. Embroidered Samplers. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1979.

- McClintock, H.P. Handbook on the Old Irish Dress. Dundalk: Dundalgan Press (W.Tempest) Ltd., 1958.

- Mitchel, Lillias, Irish Spinning, Dyeing and Weaving. Dundalk: Dundalgan Press (W.Tempest) Ltd., 1975.

- Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Proceedings, Vol LXXXVI. Edinburgh, National Museum of Antiquites of Scotland, 1954.

- Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. Proceedings, Vol LXXXVIII. Edinburgh, National Museum of Antiquites of Scotland, 1956.

- Sutton, Ann, and Carr, Richard. Tartans, Their Art and History. New York: Arco Publishing, Inc., 1984.

- Swain, Margaret. Scottish Embroidery, Medieval to Modern. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1986.

Written and illustrated by Jennet Jowan Truro (© 1990, Janet Cornwell)